The Tough Stuff That Good Journalists Are Made Of

Deep in the heart of my new novel, THE JUICE, there’s a character that’s especially dear to my heart named Ginseng Childe. She’s a journalist who’s won a Pulitzer Prize. But despite that success, it’s become more difficult for her and other journalists to expose what’s really going on in the world. And she’s gone to work for a huge media company that distorts information so that she can see behind the curtain, as it were, and really understand what’s happening within the government and powerful corporations.

There’s a cynical edge to her that I can relate to, working as a journalist myself and knowing others who are passionate reporters, fighting the good fight to get at the truth. This can be an extremely difficult thing to do.

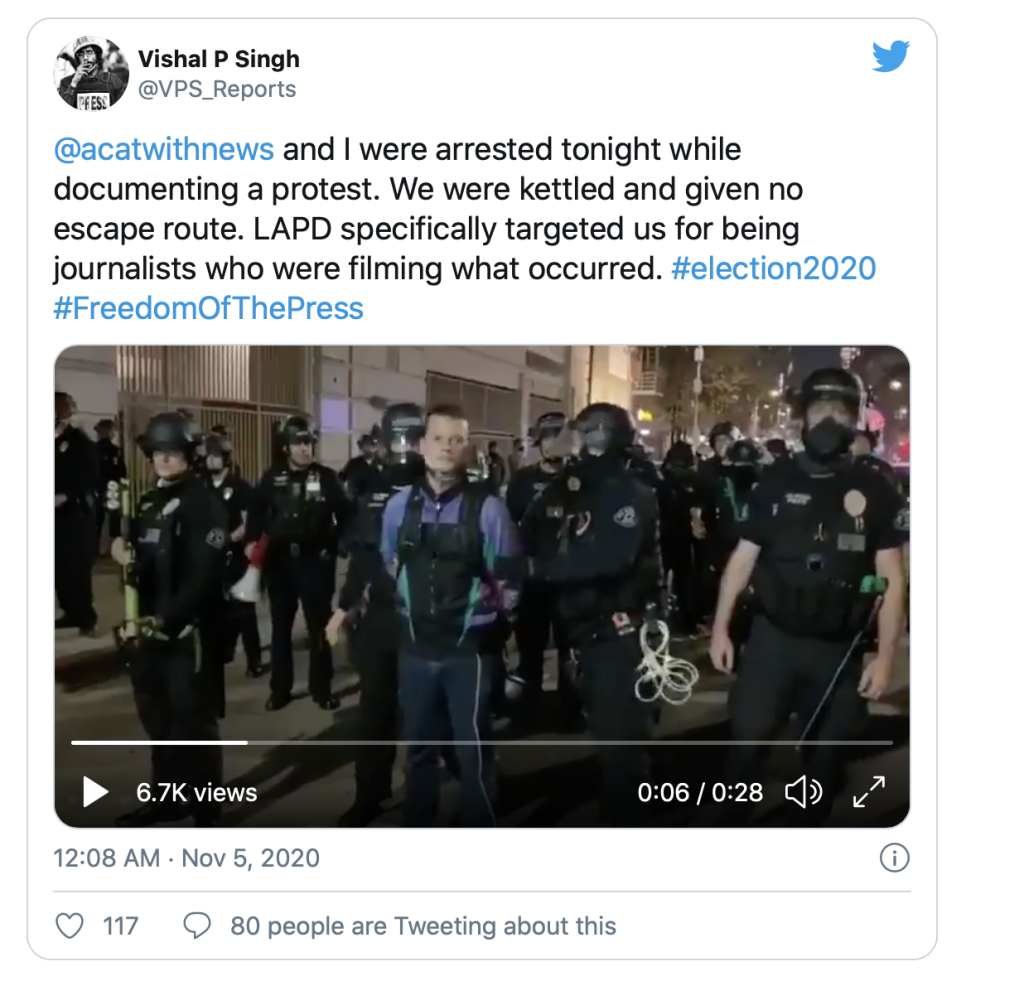

Consider that in 2020, more than 1,000 U.S. journalists faced acts of aggression that directly violated their freedom-of-the-press rights. Over 300 of them were assaulted. Some 120 were arrested. That’s according to the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker. The tweet below is featured on the organization’s site.

The number of journalists around the world who were killed, trying to do their work, was 30 in 2020, more than double 2019’s count, according to a watchdog group, the Committee to Protect Journalists.

As one of my favorite speculative fiction authors, William Gibson, once said: “The future is here—it’s just not evenly distributed.”

The ways in which journalists are blocked from reporting honest information can take less aggressive forms. I well remember hearing conversations in newsrooms when publicists and public figures tried to convince reporters that they were barking up the wrong tree—that their company or personal reputation had been wronged by what had been reported. In actuality, the news reports in question were spot on. Heck, that’s certainly happened to me.

One of my early mentors, Jack Loftus, an editor at Variety newspaper, once laughed right in the ear of one such person and hung up the phone on her. There have been times, over the years, when I wished I had the cajones to do that.

When I was at Variety, the newsroom was crammed with Formica-topped desks. The reporters on the team were a somewhat unruly bunch. And I was a bit of a strange figure in their midst, simply because I was the only woman on the editorial staff in New York.

One of the young turk reporters at the time, Kevin Goldman, would sail in each day after covering the Westmoreland Vs. CBS trial going on at the U.S. Southern District of New York Court. The legal battle was instigated by a CBS documentary about the Vietnam War, which was narrated by famed journalist Mike Wallace. (That’s Wallace, left, below with another famous CBS “60 Minutes” journalist, Morley Safer, entering the court. Photo credit: Mario Suriani.) The special report exposed evidence that military intelligence estimates were manipulated in order to make Americans believe that the war was being won. Gen. William Westmoreland, who was in the thick of the story, sued the network, Wallace and the documentary’s producer for libel.

You might say that the goal of uncovering the truth was baked into me as a cub reporter and editor. It’s not surprising, then, that one of the themes that runs through my novel, THE JUICE, is public deception.

The world I created within THE JUICE is influenced not only by those memories, but how I’ve seen media evolve. In the novel, a certain media monolith serves up artificial dreams with embedded messages to make consumers buy certain products. It’s a world where people that are mildly charming can become almost god-like, if they take a certain chemical substance, known as the Juice, which makes them extremely charismatic. They’re able to convince people to do almost anything—like fight in a war, or vote for a certain political candidate

Maybe that seems farfetched but consider that at one point the most widely available TV networks in many countries around the world were government owned and operated, and the news and information that was sometimes conveyed reflected the prevailing political parties’ views.

As a journalist covering the media, I watched that change. American programming companies made tons of money selling shows to fledgling commercial channels that eventually became quite popular and powerful in their own right. And then came commercial channels in the U.S. as well as abroad that catered to very particular points of view that largely mirror the reality that certain powerbroker wanted the general public to believe.

Subliminal messaging has been around for decades. Privacy regulations—such as the one California residents recently voted on—are attempting to guard us from companies that would like to gain access to sensitive personal information.

Don’t get me wrong. THE JUICE isn’t a dark, “take your vitamins” kind of tomb. What I aimed to create was a novel that not only delivers social commentary about media and marketing, but also a story that’s entertaining, with funny moments and others that amount to a high-octane roller coaster ride.

The people I know in large media companies aren’t evil. Many are personable, honest and whip smart, like Ginseng Childe. I don’t tar everyone with the same brush. I’ve chronicled the “adventures” of my fictional characters with love, and hopefully some nuance. I pray that the distortion of news will never reach the levels that I imagine. But dystopian, cyberpunk tales like mine have a purpose. They give us an escape from reality, but they also make us think.

As we wait for more of the future to unfold, in its unevenly distributed fashion, I hope you’ll check out my book, THE JUICE. It’s now available for pre-order in e-book form on Amazon. Hard copies will drop on the release date, Feb. 9, 2021.