Crashing Rain, Buried Truths and Growing Up

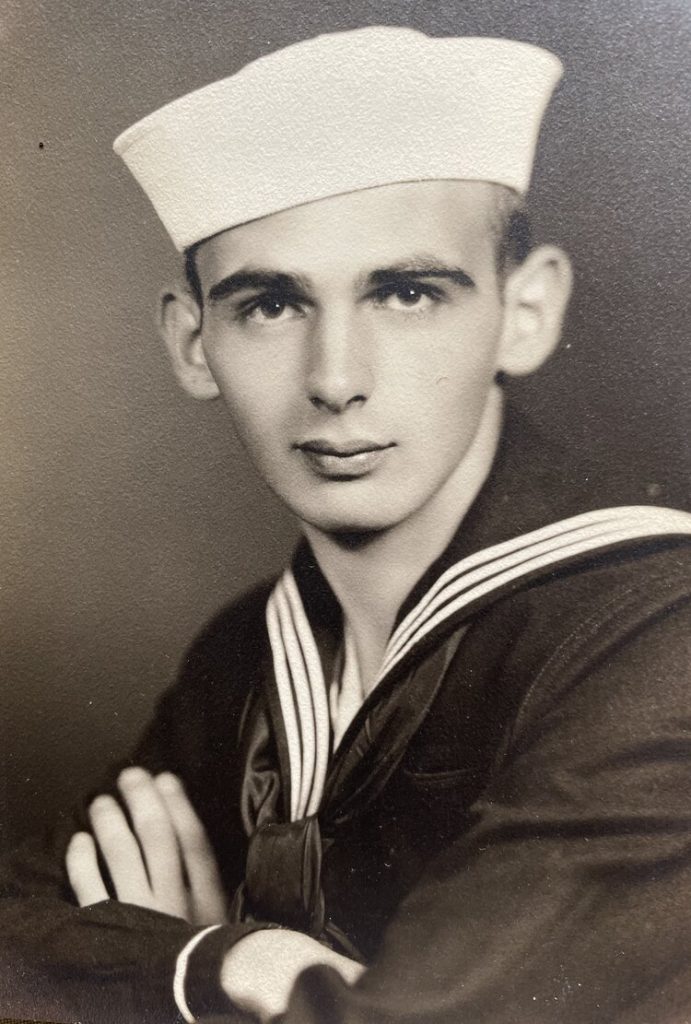

Move over, all you movie stars. That’s my dad, Walter Stilson. wearing a top I later filched.

On lazy summer days long ago, my mother, sister and I would tackle the attic, figuring out which of our possessions relegated to that deep memory space should be discarded or better organized. There were odd sticks of furniture, stacks of splashy picture magazines, my mother’s childhood ringlets in an old cigar box, and my father’s Navy uniform. (I snatched one piece of his uniform and wore it for quite some time) .

The large dark space was stuffy with an ancient wooden scent, located atop a white home with a big wrap-around, glassed-in front porch. The house was filled with my dreams and imaginings.

Much to my surprise, I got a piece of that lost time back last week when I was sorting through the contents of my bank security box. At first, the task at hand was far less intriguing than discovering treasures in the attic. I had a million other things to do that day, just wanted it to be over with. My bank branch, in the Chelsea neighborhood of New York, was closing. I had to pick up my belongings and deposit them elsewhere. It couldn’t be put off any longer.

There — among the jumble of paperwork, jewelry and a master drive of film content — was an old envelope with one single word scrawled in ink: “Save.”

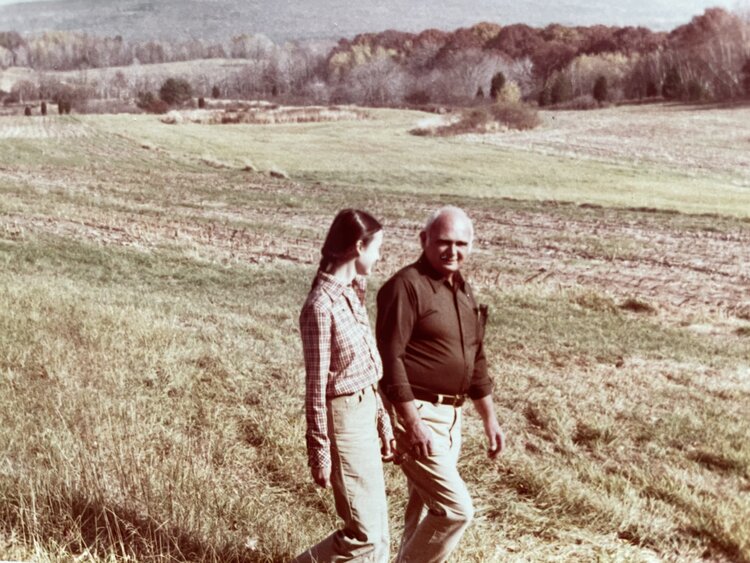

Me, around the time I wrote the essay posted here.

I knew what was inside. My stepmother had given it to me long ago. It is one of the earliest pieces of my writing. When I penned it, I was 19, going to Emerson College in Boston, and my parents had divorced. I’d given the story to my father. And when he passed away, my stepmother wanted me to have it again.

It’s not something I usually do: read one of my stories written so far back in time. But this one contains some raw truths, the essence of myself as a young woman, a sketch of my father. This one informed the final scene in my novel, THE JUICE. And I thought that some of you might enjoy reading it. So here goes:

BONDS REMEMBERED

The rain used to come pounding down on our tin porch roof just after supper about three or fourtimes a year. First dull rumbling splats in a variety of pitches would begin dotting the metal in hidden overlapping rhythms. And then, as we began to assemble underneath the opening melody, the flattened pellets of water would double in number and size, becoming insistently louder until the thousand kettledrum ceiling was combined into one gigantic roar. And everything that was two feet beyond the steps leading up to the glassed-in porch was smeared over, muddied into streaks of greyed color between the lines of water. The only part of our worlds that remained solid during these storms was this house we knew so well as our home.

My father would stand quietly near the upper right-hand corner of the porch, brooding over his pipe. His thick eyebrows were char black then, and they made a sharp cliff over his eyes, as ominous as the saturated skies overhead. His hair, which had begun to grow silver when he was 20 years old, was barely streaked with black. His cracked and hardened hands, his almost Indian red skin, his hollow but muscular body were all evidence of his long years of physical labor, and he wore them like amedal.

He walked very slowly, measuring each step, and he spoke that way too. People who didn’t know him mistook his unhurried ways and thought him dull-witted, but I knew of his hidden thunder. With one intent thought, with one powerful movement, he was capable of shaping my day-to-day life into entirely different patterns. Within this strength of his I found shelter and security. A large part of my existence thrived upon his will.

I thought I knew my father well then, but I learned later on that I hardly knew him at all. Over a cup of tea one day, my grandmother told me a story about him when he first came home from the war.

The offending photo (I think). My father is bottom row, second from right.

He’d been a navigator in a bomber. A framed photograph of the plane and the crew he was a part of used to hang on his parent’s living room wall. Once while the family was eating, conversing about nothing in particular, my father raged out of his chair, tore the photo off the wall and sent it shattering across the room.

On another occasion, my current boyfriend casually asked me if I knew that my father had been married twice. I gave him a rather shocked reply, telling him that was impossible. After our somewhat heated discussion had ended, I confronted my mother. She confirmed the story and told me that my father had asked her never to mention it. So for 17 years, it had been kept secret from me. She must have said something to my father, for he took me aside not long after that. This first wife of his had annulled their marriage less than a year after they had been married. He had loved this woman very much, and the whole affair had wounded him deeply.

And so, after this second discovery, I began to realize how unaware I was of his hidden turmoils and remembrances. The only period of his life that I could even partly be sure of was the fraction of time that I had spent with him.

During these raging downpours, the two of us would stand, silent companions on the theatrically lit porch. Soon, after my mother had stacked the last pan in the dish rack, she would join us, a warm sudsy dishcloth in her hand. And eventually, I would sit in a creaking rocking chair, hoisting my feet on a windowsill. They would sit beside me then, and together we’d scrutinize the drizzly view, talking lightly.

When I had finally wriggled into my blanketed tunnel later on that night, I’d listen to the roof’s lullaby on the other side of my bedroom wall. And feeling so protected from the liquid darkness there, I would begin my nightly stories of cavemen in warm, soft hibernation and of richly clothed Elizabethan women bathed in thick furs, while outside the water crashed on.

That was when I was 10, 11, 12, and all the way up to 17. Now I’m 19 and the rain outside my windows is ever so silent no matter how hard it storms.

My mother told me some time ago that the people who live in our old house were planning on tearing off the porch. For some reason, I had never noticed that it sagged. I went to see the house yesterday, dreading its new appearance. Yet, at the same time I hoped that it had changed, so that memories of my father wouldn’t start weighing down my throat.

Much to my relief the porch was still there with what looked like a fresh coat of paint on it. Perhaps the rains convinced the new owners that it should stay.